Abstract

Background: Individuals in stressful work environments often experience mental health issues, such as depression. Reducing depression rates is difficult because of the persistently stressful work environments and inadequate time or resources to access traditional mental health care services. Mobile health (mhealth) interventions provide the opportunity to deliver interventions in real time, in the real world. In addition, the delivery times of interventions can be based off of real-time data collected with the mobile device. To date, data and analyses informing the timing of delivery of mhealth interventions are generally lacking.

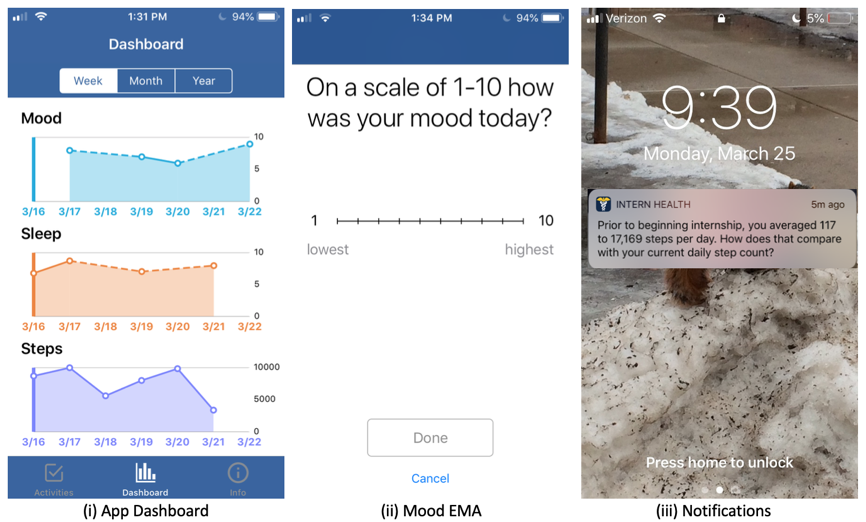

Objective: The study investigated when to provide mhealth interventions to individuals in stressful work environments in order to improve their behavior and mental health. The mhealth interventions targeted three categories of behavior: mood, activity, and sleep. The interventions aimed to improve three different outcomes, weekly mood (assessed via a daily survey), weekly step count, and weekly sleep time. We explored when these interventions were most effective, based on previous mood, step, and sleep scores.

Methods: We conducted a 6-month micro-randomized trial (MRT) on 1,565 medical interns. Medical internship, the first-year of physician residency training, is highly stressful, resulting in depression rates several folds higher than the general population. Every week, interns were randomly assigned to receive push notifications of a particular category (mood, activity, sleep, or no notifications). Every day in the study, we collected interns’ daily mood valence, sleep, and step data. We assessed the causal effect moderation by previous week’s mood, steps, and sleep. Specifically, how did the effect of notifications containing mood, activity, and sleep messages change based on the previous week’s mood, step, and sleep scores? Moderation was assessed with a weighted and centered least-squares estimator.

Results: We found that previous week’s mood negatively moderated the effect of notifications on the current week’s mood with an estimated moderation of -0.052 (P = .001). That is, notifications had a better impact on mood when the studied interns had low mood in the prior week. Similarly, we found that previous week’s step count negatively moderated the effect of activity notifications on current week’s step count with an estimated moderation of -0.039 (P = .01) and that previous week’s sleep negatively moderated the effect of sleep notifications on current week’s sleep with an estimated moderation of -.075 (P < .001). For all three of these moderators, we estimated that the treatment effect was positive (beneficial) when the moderator was low and negative (harmful) when the moderator was high.

Conclusions: These findings underscore that an individual’s current state meaningfully influences their receptivity to mhealth interventions for mental health. Timing interventions to match an individual’s state may be critical to maximizing the efficacy of interventions

Keywords

mobile health; smartphone; depression; mood; stress; push notification; micro-randomized trial; moderator